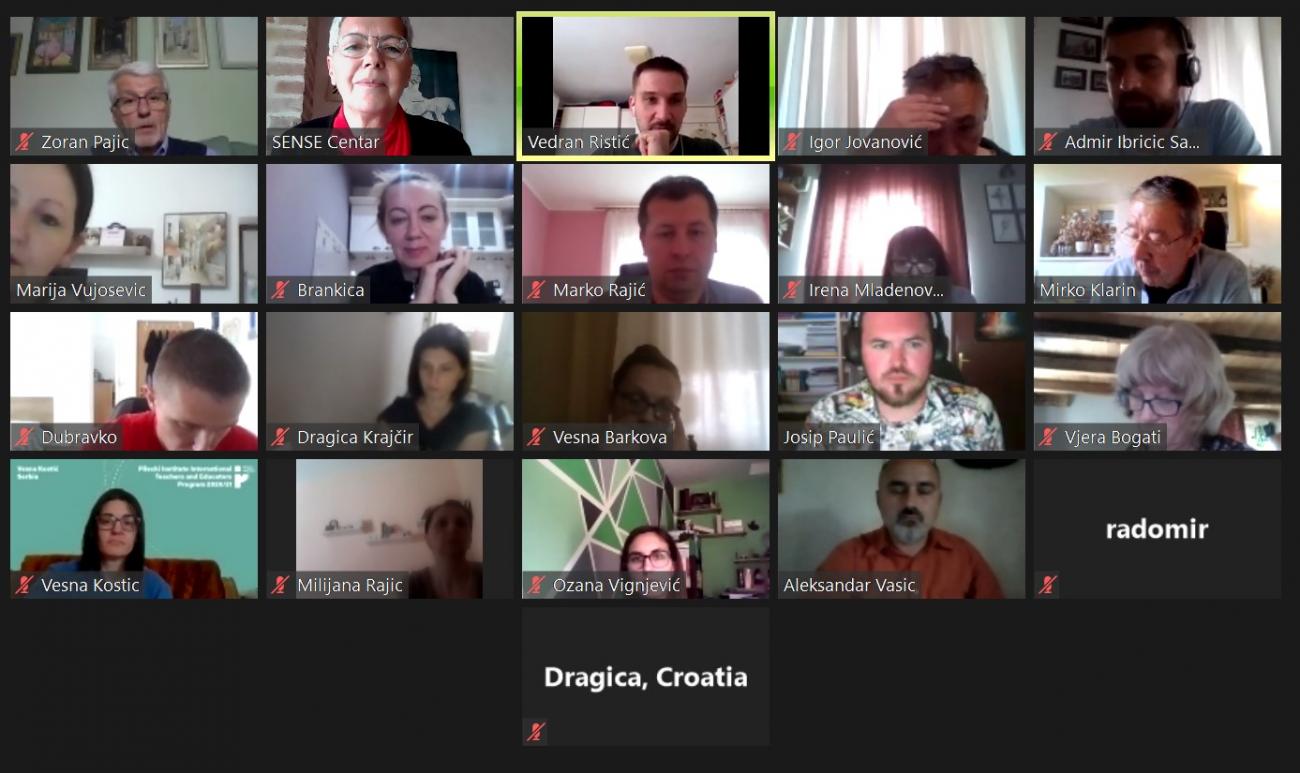

The conflicts of the recent past need to be taught about impartially if we want to avoid future conflicts, assessed history teachers from Croatia, Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, Montenegro and Macedonia participating in the webinar organized by SENSE Center and HUNP - the Croatian History Teachers' Association.

The key source of unbiased information on the wars of the 1990s is the evidence gathered and the verdicts reached before the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), participants in the webinar pointed out .

The first webinar in the series called "De-weaponizing History - How to Prevent History Teaching from Becoming a Continuation of War by Other Means" was held in January and covered the topic of destruction of cultural heritage and identity. This, second one, was called "Tribunal for beginners".

The points of discussion were: to what extent has the Tribunal been presented in history textbooks and school curricula in the region; why, how and with what expectations was the Tribunal created back in 1993.; how the international community and ex-Yugoslav states approached the Tribunal; and how it managed to survive despite an initial neglect of its founders and a lack of cooperation by the ex-Yugoslav states.

The keynote speaker at the second webinar was professor Zoran Pajić, who taught international law at the University of Sarajevo and The King's College in London. He pointed out the crucial role that history teachers play in developing understanding among the young that they must distance themselves from the wrongful past politics of their countries and nations.

Thanks to the Nürnberg trials after The Second World War and the facts established in the process, an awareness has been born about the importance of a detailed presentation of evidence, said Pajić. Leaders of some victorious countries, like Britain's Winston Churchill, suggested that Nazi leaders should be straightforwardly executed because it was well-known what they had done. However, the other option prevailed - that they should be put to trials. During those trials, Nazi crimes had been minutely documented, which in turn helped the Germans become aware of everything Nazis had done and it led to denazification of Germany.

"Trial based on prima facie evidence, a general knowledge about events and perpetrators, is entirely unacceptable in modern democracies. A thorough, minute presentation of evidence is demanded, as is respect of the rights of the accused", he said.

The story of the ex-Yugoslav Tribunal is very similar. It was created with skepticism, even by those who voted for its creation. However, it grew into an efficient institution which thoroughly investigated the events. "The findings of the Tribunal must be respected and the young have to be taught about them, so that they understand there is something called generational responsibility for the deeds of former officials, but also for them to be able to distance themselves from those deeds", said Pajić.

The webinar participants were shown several videos from SENSE's substantial archive, produced during its 20 years of the Tribunal's coverage. They included a section of the documentary "Against All Odds", which tells about the uncertain process of the creation of the Tribunal and its "labor pains", and SENSE's TV reports (excerpts TVT 446, TVT 523) showing international experts and representatives of victims from the region discussing what the Tribunal achieved or did not achieve and what impact it had in the region and internationally. Finally, as a sort of treat, a short film was shown, called "A Funny Side of the Tribunal", part of SENSE's weekly TV chronicles.

"We cannot expect the Tribunal to take on the entire process of indemnification for the victims. It takes more than legal justice", professor Pajić said in conclusion. A restorative justice process (or transitional justice process) has to take place instead, establishing why the conflicts and crimes happened in the first place, reconciling opposite views of the events, providing compensation and empowerment of victims.

The participating teachers formed three working groups to discuss methods of teaching primary and secondary school children about the work and achievements of the Tribunal. They concurred that acquiring knowledge about the Tribunal is imperative, particularly for secondary school students. In reality, very little is being taught about the conflicts of the 1990's in schools all over the region. "Children ought to know more about the facts the Tribunal established, about the necessity of facing the past and about the principles that trial brings greater justice then revenge and that judicial processing of crimes will avert future conflicts", said Vedran Ristić, coordinator of a working group.

Teachers came up with a number of ideas to enhance the teaching about the Tribunal and its heritage, from classroom simulation of a trial session, to summer camps, school trip or the creation of a joint regional textbook archive.